Before my travel to Europe, I promised an analysis of the short- and middle-term prospects of the economy of New Zealand. As a rule of thumb, New Zealand’s economy prospers according to global conjunctures, so it is the growth prospects of the global economy that matter. To perform such an analysis, I recall a former paper about cyclical global growth. The suggestions of the analysis are not encouraging. In the short term, the global economic mood seems to get worse in the next decade. However, after 2033, there is a good chance for more substantial growth. This growth will be even more solid after 2045.

The cyclical patterns of economic growth were the topic of discussion after a Russian statistician, Nikolai Kondratieff, published his paper in 1922. In the paper, he predicted that Western capitalism would get into a crisis within the coming decade. He proved to be correct. Although he was accurate and gave hope to the Soviet regime, Kondratieff still got into prison for his economic views. The reason was simple: he also predicted that Western capitalism would overcome the crisis and might become even more prosperous. Up until today, he has been the only economist who got into prison owing to his views. After his prediction that Western economies would recover proved true, he died in a Labour camp in 1936.

Kondratieff examined long-term interest rates and the production and price evolution of coal, steel, wheat, and woollen, and he based his hypothesis on these long-term trends. His main claim was that liberal democracies that implemented free-market capitalism experience 50-60 years-long waves of economic growth, and in the upswing phase of the waves, social revolutions are more likely. In his time, his research was popular, and others, such as Simon Kuznets and, to an extent, Joseph Schumpeter, also worked on the elaboration of long-term waves of economic development. Nevertheless, Kuznets emphasized the relevance of the 20-25 years-long fluctuation of infrastructure investments owing to the housing needs of new generations, and Schumpeter derived the fluctuations from the varying waves of optimism-pessimism of those who fund the investments that are the roots of developments.

By the 1980s, mainstream economic research abandoned the examination of long-term trends because it seemed that the price and production tendencies no longer showed cyclical patterns. Among the main researchers, I highlight Solomos Solomou, who proved that the long waves that Kondratieff identified had been the consequences of the catch-up of new European nation-states such as Germany to the most developed countries of the late 19th Century, Great Britain and the United States.

As a surprise, military and social experts started the research on the long-term economic fluctuations at the beginning of the 2000s. A security conference was dedicated to this topic in Madrid in 2004, where Russian scientists were invited alongside experts from NATO member states. In this wave of research, I met the works of George Svachulay, who developed a methodologically grounded model for the evolution of human thinking (philosophy) and published his research in 2007 (it is available only in Hungarian). Among many cyclical patterns, he identified the time interval of humanity’s reformations of religious thinking (588 years – Buddha and Zarathustra 552 BC; Christ around 36 AD; Mohamed in 624, etc.). Within this timeframe, there are three 196-year-long periods for philosophical reflection, when public experience about social practices creates awareness. This 196-year-long period can be divided into four 49-year-long intervals, which are the length of various ideologies and human attitudes alongside which generations organise their life.

This wave of research on long-term economic and social trends was partly triggered by the works of Angus Maddison, an economic historian, who attempted to estimate the countries’ GDP data in terms of purchasing power parity. He established the Maddison Project, a research agenda that the OECD first operated. Now, the project is run by economists in the Netherlands; their leader is Jutta Bolt. Maddison first published his time series in 2003. In this first publication, he could assess the GDP for all countries for 1820. However, it was not a continuous time series for all countries. The time series ended in 2001.

This dataset was crucial for researchers who intended to analyse the long-term economic trends. Later, in 2014, the Maddison Project (after the passing of the founder, Angus Maddison) published an extended and revised dataset. This included GDP data between 1820 and 2008, so the effects of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) were included too. The reason why the start of the period is 1820 is simple: it was during the Napoleonic wars when states realized the significance of macroeconomic figures, and the coherent data collection could start by the 1820s.

In my research, I could use both datasets.

The key results

Economists have to apply spectral analysis to filter out which cyclical component (a sinus wave) has the largest contribution to the variance of the time series. When we find the given cyclical component, it is crucial to test whether the contribution to the variance is still by chance or if there is a significant correlation with the identified cyclical component.

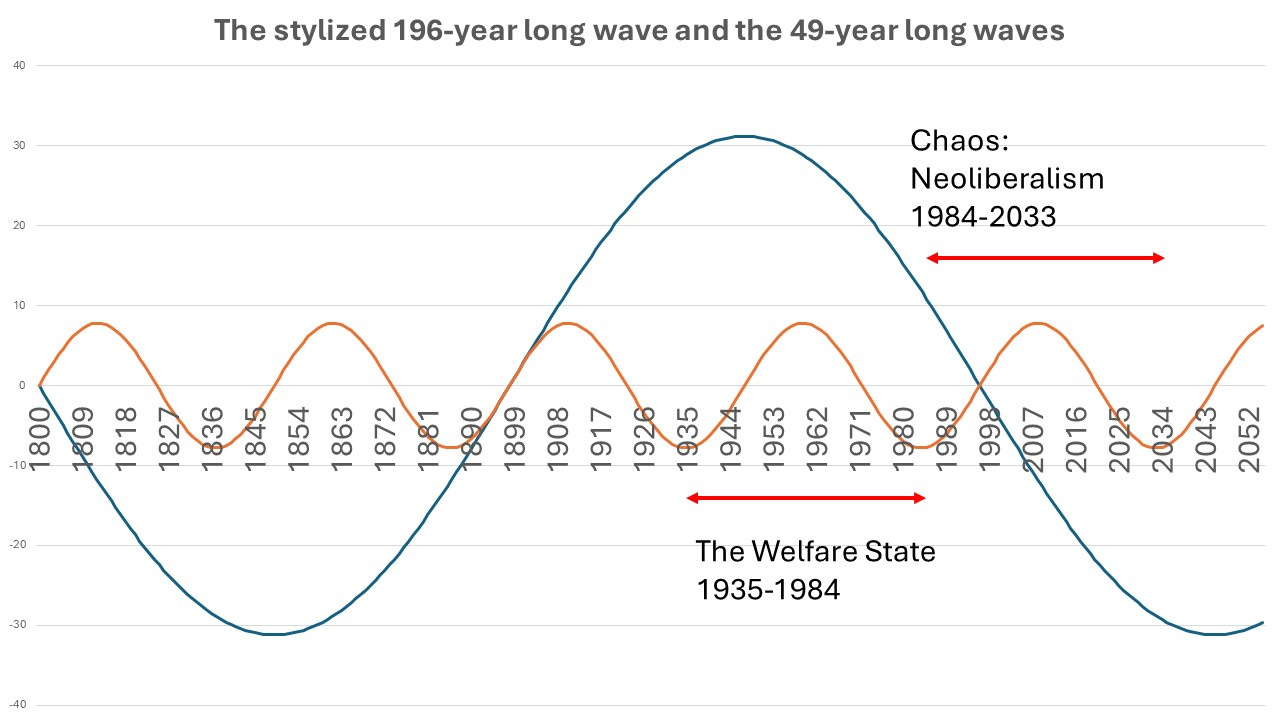

To my surprise, there was no significant presence of any cyclical components in the individual countries’ datasets. (I checked the 23 economically most relevant countries.) This confirmed the former research results, both for the time series ending in 2001 and 2008. However, for the global data, the research of the time series confirmed the existence of the 196-year-long cycle. The 180-year-long period was the most significant in the case of the time series ending in 2001. The 188-year-long cyclical component had an even greater contribution to the variance. Finally, in 2019, I could revisit the research with the time series ending in 2016. The 196-year-long cycle was the most significant in comparison to the former results. (See the first graph above.)

Unfortunately, the Maddison Project changed their methodology after 2020, the new datasets are not applicable for further comparisons. Nevertheless, I believe, the 196-year long cycle is crucial. Let’s take a look at the visual representation of this cycle (above) and what it suggests for the future!

As the curve suggests, global average GDP growth will likely fall until 2045. Then, a new upswing period will kick in. The graph above shows further crucial empirical evidence, too.

The main upswing period of the past centuries started in 1849 and lasted until 1947. This was a period when natural science gave optimism to most people, inventions created trust for politicians too to finance not just those inventions but major wars too. In a weird sense, Kondratieff’s notion that during the upswing periods of cycles, there are wars more often is right. But, the upswing period is actually 98 years long, not 25-30 years, as Kondratieff thought. During the downswing periods, there are fewer wars. Therefore, the bad news that until 2045, humankind will not see another general upswing is the good news for the near future: we do not have to expect another open world war. None of the great powers is optimistic enough to initiate such a conflict.

Here, I will highlight another aspect of the global time series. The highest GDP growth historically occurred between 1947 and 1971, when the world saw the post-war reconstruction and the zenith of the welfare state. Although the period between 1922 and 1947 was similarly strong in terms of opportunities, the volatility of the Great Depression and the Second World War diminished its potential. After the beginning of the 1980s, when neoliberalism became the mainstream economic regime, global growth could not return to the previous levels in terms of purchasing power. What’s more, it contributed to its further fall.

It is worth describing the effects of the 49-year-long ideological cycles to provide some more specific forecasts about the future of the global economy. Even though these did not prove to be significant, the ideologies are the personal belief systems that provide guidance for the individual. The 196-year-long cycle of philosophic reflection is not personal; ideologies are.

What comes after neoliberalism?

The next graph shows the stylized sinus curves relevant to our discussion. The long wave goes into negative territory first, then, after 1898, it is in positive territory; meanwhile, after 1996, it is negative again. The shorter, 49-year-long sinus curves start in positive territory first, then turn into a negative domain.

Unfortunately, I have not yet deciphered the reason why the long wave started in negative territory. Nevertheless, when I analysed the combined curve (the sum of the two sinus curves), I understood the relevance of the shorter curve. As in the case of the sinus curves, the local minimum and maximum points, as well as the inflexion points, are critical moments. In inflexion points, the curve changes whether it is bending upwards (convex) or downwards (concave), and it is at these points where it is the steepest.

In terms of the not-too-distant past, in 1996, the 49-year-long sinus curve was trending upwards; however, at a slowing pace, the curve was concave. During 2008 and 2009, it reached a local maximum and was turning downwards. This coincided with the GFC. This curve was trending downwards with the largest pace in its next inflection point during 2020 and 2021. It coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic. Because the longer, the 196-year long sinus curve was trending downwards in 2020, therefore, that year could not bring anything else than a huge crisis. Similarly, the local minimum of the shorter, 49-year-long curve will signify something. By 2033, this curve will reach its local minimum. This will mean a new economic ideology and regime that will replace the current neoliberal ideology.

The question is what sort of new ideology will appear. It might be easy to expect that after neoliberalism, we may have another phase of the welfare state. However, it is unlikely. The dominant ideology will be defined by the mainstream political trends.

It is essential to note that in New Zealand’s case, the alignment with the global trends is quite shocking: in 1935, the First Labour Government established the Social Security Act, which was the beginning of the welfare state. In 1984, the Fourth Labour Government initiated the neoliberal reforms that became known as Rogernomics. This economic regime will certainly be replaced in 2033. Little does Brooke van Velden, the current employment relations minister and the strongest proponent of neoliberalism in New Zealand, know that she has a certain historical role: She is creating a strong public momentum that opposes neoliberalism and will eventually sweep this ideology away for good. (The similarity of her historical role to the one of Robert Muldoon’s is staggering: Muldoon was a highly controversial personality, and he promoted those state-organized investments, the “Think Big” projects, that eventually created the momentum for neoliberalism.)

If it is not a novel version of the welfare state that will replace neoliberalism, then what ideological guidance will we have that would be the basis for a new economic framework? To answer this question, it is relevant to outline further details about those cyclical periods that Svachulay defined. The 196-year-long cycle is the time of philosophic reflection. Between 1800 and 1996, the philosophic reflection provided us with knowledge about globalisation. By 1800, the world had become globalized in the sense that all continents had become interconnected. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the scientific literature identified globalisation, and from then on, political forces consciously attempted to foster further globalisation, strengthening diplomatic, trade, and cultural relations.

The 196-year-long cycle is one-third of the age of religious reformation, the 588-year-long period. The three 196-year long period is divided as the Hegelian dialectic requires, the three periods are thesis, antithesis, and synthesis respectively. Between 1800 and 1996, the thesis period happened. This was the establishment of globalized relations coupled with the spread of democratic institutions and market capitalism. After 1996, however, the antithesis of this period started. Therefore, it is likely that globalisation will be reversed to a certain extent between 1996 and 2192.

The 196-year-long cycle is also divided into certain periods: four 49-year-long cycles. The four periods are early antithesis, mature antithesis, early synthesis, and mature synthesis. Later, for the new 196-year periods, the mature synthesis becomes the thesis that will be opposed by the early antithesis ideology. Importantly, Svachulay warned that the first 49-year-long period, the early antithesis, is a chaotic historical period.

It is relevant to analyse the four 49-year-long cycles between 1800 and 1996.:

1800-1849: chaos. Absolutistic dynasties are fighting against early nation-states. Political elites are opposing other political elites.

1849-1898: the evolution of nation-states. Political elites of certain countries respect other nations’ political elites. Besides, the capitalist-capitalist competition is limited, and antitrust legislation after the first global economic crisis of 1873-1880, the Long Recession. Liberalism attempts to reclaim individual freedom, which was an early element of the welfare state (pension systems).

1898-1947: The re-extension of national markets. Nationalistic policies were coupled with the establishment of the welfare state after the Great Depression. Capitalist-worker relations are controlled, favouring workers to an extent (bureaucratic employment was established in this period, bringing clear career paths for employees).

1947-1996: The zenith of the welfare state and early neoliberalism. The welfare state faces a crisis due to limited natural resources.

Between 1996 and 2192, the achievement of globalisation will be reversed; therefore, we will find tendencies to isolate specific regions from one another. We can see this trend after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (border closers, restricting the movement of people, WHO initiatives for possible next pandemic, etc.). The war in Ukraine was an explicit example of isolating a region (Russia and its allies) from other regions. In this endeavour, the European Union was the key stakeholder. Besides, we can already see signs of trade relations diverging from China. This trend is not strong yet, however.

This period between 1996 and 2045 is chaotic. In the beginning, we still experienced the full swing of neoliberalism and the burgeoning of free trade agreements as signs of intensifying globalisation. This is why it is shocking on a surface level, why regions and alliances tend to isolate their economies from other regions. However, it can be understood by using the thesis-antithesis-synthesis model.

For these overarching causes, the following political ideology of democratic regimes will focus on defending democracy for specific regions. In this attempt, this ideology cannot be thoroughly liberal; it will be more similar to nationalism. This ideology will not support migration from the opponent regions. Nevertheless, to maintain their attractiveness to voters, these democratic countries will likely improve their welfare systems, too. A more equal distribution of incomes will be the aim. In this sense, it will be more social-democratic, too. The more equal distribution of incomes will create growth opportunities after 2033. So, strengthening economic growth might appear earlier than 2045. The only problem is that by 2033, trade routes should be diverted from the existing China-centred system, and this diversion of trade will have negative economic consequences. So, until 2033, New Zealand will face more difficulties. The situation gets worse before it improves.