Between the 12 and 16 August, there was relevant news about New Zealand’s foreign policy shift. One concerned former defence minister Andrew Little’s speech at a conference in Christchurch; the other was related to the Prime Minister’s address to the Lowy Institute in Sydney. It is not just foreign policy that connected the two events, but the advisors in the background and the lobby groups who have immense direct and indirect influence on forming New Zealand’s foreign policy. It is not possible to emphasize how wrong it is to see a Prime Minster with a schoolboy’s experience and think tanks who have no respect for public opinion.

Of the two critical problems, Christopher Luxon’s amateurish speech in Sydney and the message from think tanks to a conference delivered by Andrew Little, the one of the Prime Minister’s is the less critical. He can easily be voted out and replaced. The influence of unelected think tanks is immense, and I do not know of any solution. Let’s start with analysing Luxon’s speech!

Excellent at a university exam – failing as a politician

Luxon’s main message can be summarised shortly: New Zealand’s foreign policy reset is the alignment with the interests of the Anglo-Saxon great power (the United States). He repeated that New Zealand [his government] believes that AUKUS is crucial to regional security, and the government was exploring how New Zealand could participate in Pillar II. By illustrating this policy shift, Luxon made his usual (and annoying) mistakes when he used glorifying terms and new ones when speaking about theoretical aspects of foreign policy that may be interesting in a university seminar. However, politicians should not discuss or mention them in any conversation.

To illustrate my arguments with quotes, I used Geoffrey Miller’s piece on the Democracy Project’s substack on 16 August. Regarding glorifying statements, Luxon mentioned that his minister for foreign affairs, Winston Peters, was ‘among the most activist and impactful of New Zealand’s foreign ministers in a generation’ and was ‘reshaping our foreign policy’. Also, discussing the Pacific region, Luxon said he believed New Zealand and Australia would be ‘steadfast partners in support of our fellow Pacific Islands Forum members’. Finally, Luxon was also straightforward about his ambition in defence and said we [New Zealand] want to be a force multiplier for Australia’.

Those who know my piece about the psychological term escapism and what is the similarity between Jacinda Ardern and Christopher Luxon also know that once it is recognised, it is annoying. Here, the problem is the same: calling Peters as someone among the most activists is a bit odd. It gives praise but also presents Peters as a miracle man, who he isn’t. The term ‘steadfast partners’ is also quite annoying, the question emerges why Luxon could not just say that Australia and New Zealand are committed to secure the Small Island Nations in the Pacific region? Finally, arguing that New Zealand wants to be a force multiplier for Australia is nonsense. On the one hand, the term ‘force multiplier’ refers back to the Middle Ages, where strongholds were the centres of defence lines. Any stronghold served as a force multiplier to the troops inside. It is not certain how New Zealand could be a stronghold for Australia. Nevertheless, on the other hand, the word ‘multiplier’ can also refer to the number 1.01, which is a multiplier too – a rather small one. So, these glorifying words do not help the Prime Minister establish an image of a reliable politician internationally.

When Luxon engaged in arguments that were mostly theoretical, he presented himself as a caricature of a politician. Here, it is sufficient to describe three examples of why these theoretical arguments are critically problematic. First, he said something completely wrong when he argued that ‘we can’t achieve prosperity without security’, and when he elaborated on this, mentioning that the war in Ukraine had shown ‘you can’t simply have separate economic interests from your security interest.’ Unfortunately, economic prosperity correlates with defence spending. Globally, economic growth was the strongest before the Second World War and then between 1945 and 1971, when the nuclear arms race and space programs were rampant.

Consequently, the sense of security was lower, and there were wars (for example, in Vietnam). Besides, Luxon's argument is a very poor representation of traditional realist thinking: economic interdependency only creates conflicts. Simply put, it is bulldust. Nevertheless, it was a phrase a prime minister might still say. It can be accepted as justification for policies.

However, second, Luxon highlighted that Wellington’s support for Ukraine and the involvement in a US-UK-led coalition conducting airstrikes against Houthi rebels in Yemen are the representation of consistency in foreign policy: ‘You can believe your values, but you’ve actually got to follow it through with actions as well’. This is wrong, too, and this is an example of what a politician can never say! Why is it wrong? A country can only stand up for values rhetorically, especially regarding the security of regions. Why could he not say it? Even though it is imperative to perform consistent actions with rhetoric, if a politician says this, that makes him (them) look like consistency is their only motive for the specific policy. In these cases, why could not Luxon just say that New Zealand intended to contribute to the international efforts to secure the world order in these conflicts? It blows my mind…

Thirdly, most problematically, Luxon expressed that he believed the days of New Zealand’s ‘independent foreign policy’ were over. Besides, he even made a joke about the concept of independence in foreign policy, describing it as ‘nonsense: there are 195 countries in the world with eight billion people in it, and each of those 195 countries also has an independent foreign policy’. Although whether a country can be independent in the international system is a good question for a policy tutorial at the 200-level, a prime minister should not engage in discussions about it.

Theoretically, anyway, Luxon is right. The reason for this is simple. New Zealand has the largest latitude in forming foreign policy due to its distance luxury. In technical terms, New Zealand is the least likely case to be influenced by foreign actors in foreign policy. However, because experts and politicians have to consider great powers’ interests in forming policy, this shows that New Zealand is also influenced by them. Because New Zealand is the least likely country to be influenced, it is logically proven that no country can be independent.

Nevertheless, it is forbidden for a politician to say this! Why? By saying it, the politician practically says that he(she) is just a puppet. Luxon has just done that. It is incredible why no one in his advisory team could not tell him that regarding the alignment with the United States and the other Anglo-Saxon countries, Luxon should say only that “in defence and security issues we intend to cooperate with like-minded countries, with whom we share the same values and beliefs in democracy.”

The inability to brief Luxon about what he could say and not say concerning foreign policy is part of a broader problem what Bryce Edwards described in another opinion piece on the Democracy Project last week (14 August): the influence of think tanks and lobby groups over forming New Zealand’s foreign policy.

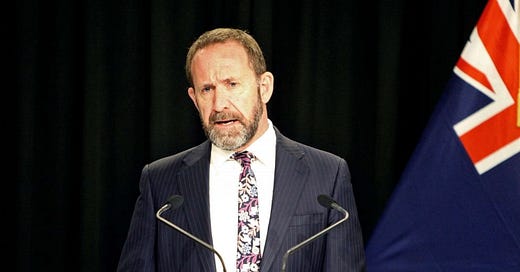

Who convinced Andrew Little to become hawkish?

At a conference about New Zealand’s possible role in the Indo-Pacific region at Canterbury University, Andrew Little delivered a speech in which he presented China as a threat to the region and favoured the option of New Zealand joining AUKUS in one form or another. Little also mentioned that the world has changed, and the security environment is not the same as it was 20 years ago. Moreover, Little referred to Helen Clark by saying that he “strongly disagrees with those who argue that China is a benign presence and poses no threat.”

With the provocative speech, Little aligned himself with the current government. However, it is possible to argue that, in a way, being provocative is out of character for Little. He has always been respectful to others. Besides, even though he is regarded as hawkish against China, it does not seem likely that he took such a stance on his own. Little does not seem to have such strong critical and independent thinking skills.

Throughout his whole career, he was best as a mediator, first as a union representative and later as a lawyer. His capacity to deliver messages to others was even used by his colleagues. It is not a preferred task by a politician to deliver hard messages. We can see this in an example from 2021. During the Delta lockdown, it was not the prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, who described those modelling scenarios that showed a dramatic picture of the virus’s spread, but but Andrew Little, then minister of health.

This time, it is also likely that someone or an interest group convinced him to deliver a strong message. It is doubtful that Little, who retired from politics after the election in 2023 and now works as a lawyer, would be better informed about foreign policy issues than a year ago. He was asked and informed by other(s) about what he had to say. Among the conference funders, we find the US Government, the Taiwanese Government, a Taiwanese think tank (Crossboundary Management Education Foundation) and the New Zealand Government’s Asia New Zealand Foundation. Although it is obvious that these sponsors all have influence over the speeches that are presented at the conference, it is likely that Little does not have direct ties with them because he works at Gibson Sheat Law Firm.

Besides the think tanks, individuals can have at least informal and maybe even direct influence over the speakers. In Little’s case, there are a number of people with whom Little had work relations, who might still be close to him, whose words matter to Little, and who are still working in an environment dealing with security and foreign policy issues. However, the possible circle of people who might have convinced Little to become hawkish can be reduced. These people must be hawkish themselves, too, and cannot be identified with any partisan group.

Have you got any tips?

I have mine who might be “responsible” and I am happy to share if there are at least three people who signals interest!

“Force multiplier” has nothing to do with strongholds or fortresses and everything to do with structuring NZ’s armed services so as to complement our likely allies, principally Australia. An example might be arming our navy with anti submarine weapons while Australia’s looks after air defence. Little and Luxon have identified NZ’s national interests and the government now needs to fund and structure our armed forces accordingly.